Pattern Matching & Lazy Evaluation

Introduces pattern matching, and explains how to implement lazy evaluation and streams in Racket.

Pattern Matching

We often need to branch the computation according to the content of a data structure. This can be tedious, especially if the data structure is complex. We must extract the determining values and then branch the computation based on the corresponding equality tests. Consider a simple function computing perimeter of a given 2D shape. There are three types of shapes: rectangle, circle, and triangle. The size of the rectangle is specified by its width and height, the circle by its radius, and the triangle by the lengths of its sides. Thus the input is given as a list whose first member is a symbol among 'rect, 'circ, and 'tri followed by respective numeric parameters. E.g.,

'(rect 3 4)

'(circ 5)

'(tri 3 4 5)The function computing the perimeter of such shapes can be implemented as follows:

(define (ugly-perim shape)

(define type (car shape))

(cond

[(eq? type 'rect) (let ([width (cadr shape)]

[height (caddr shape)])

(* 2 (+ width height)))]

[(eq? type 'circ) (let ([radius (cadr shape)])

(* 2 pi radius))]

[(eq? type 'tri) (let ([a (cadr shape)]

[b (caddr shape)]

[c (cadddr shape)])

(+ a b c))]

[else (error "Unknown shape")]))Line 2 extracts the type of the shape. According to the type, we branch the computation. Each branch extracts the respective numeric parameters and then computes the perimeter.

Similar tasks might easily lead to nested conditionals intertwined with the value extraction. Fortunately, most modern functional languages provide a pattern-matching mechanism that simultaneously allows branching and value extraction. The syntax for the pattern matching is similar to cond:

(match exp

[pattern1 exp1]

[pattern2 exp2]

...)The value of exp is successively matched against the patterns. The corresponding expression on the right-hand side gets evaluated if a pattern matches. There are many types of patterns one can use. For a complete list, see the documentation. I only mention a few possibilities. Consider the following code

(struct point (x y))

(match exp

[0 'zero]

[1 'one]

["abc" 'abc]

[(point 0 0) 'point]

[(? string?) 'string]

[(and (? number? x) (? positive?)) (format "positive num ~a" x)]

[_ 'other])The above code shows how to match against values of basic data types. Note that we can test the exp value to be a concrete numeric value (Lines 4-5), a string (Line 6), or a concrete instance of a structure (Line 7). The pattern starting with ? matches if the following predicate is true for exp (Line 8). The predicates can be further combined by logical operations (Line 9). The last pattern (Line 10) matches against any value.

The following code introduces pattern matching for lists.

(match lst

[(list) 'empty]

[(list x) (format "singleton (~a)" x)]

[(list 'fn ys ...) (format "fn and rest ~a" ys)]

[(list (list 'fn args ...) ys ...) (format "fn with ~a and rest ~a" args ys)]

[(list 1 2 ys ... z) (format "1, 2, rest ~a and last ~a" ys z)]

[_ 'other])Line 2 matches if lst is empty. Line 3 matches if lst contains exactly one element. Moreover, its value is bound to x. Line 4 fires if lst has the first element, the symbol 'fn. The three dots behind ys mean that the list of remaining members, i.e., (cdr lst), is bound to ys. Line 5 shows that we can even match nested lists. Line 6 matches if lst has at least three elements and starts with numbers 1 and 2. The last element is bound to z, and the elements between 2 and z are bound to ys.

With the above tools, we can simplify the function ugly-perim as follows:

(define (nice-perim shape)

(match shape

[(list 'rect width height) (* 2 (+ width height))]

[(list 'circ radius) (* 2 pi radius)]

[(list 'tri a b c) (+ a b c)]

[_ (error "Unknown shape")]))Lazy evaluation

I already mentioned in Lecture 1 that Racket's evaluation strategy is strict. More precisely, whenever we evaluate a function call (f exp1 exp2 ... expN), all the expressions f exp1 exp2 ... expN are evaluated first (from left to the right).[1] Once all the expressions in the call are evaluated, we can evaluate the call itself. Either f is a primitive built-in function so that its resulting value can be directly computed, or the definition of f is expanded, and its body gets evaluated.

There are a few exceptions to this evaluation strategy. In particular, conditional expressions get evaluated differently. For this reason, if and cond are said to be syntactic forms rather than functions. Other examples where the strict evaluation strategy does not apply are logical operations and, or. Their arguments get evaluated from left to right. Once any and's argument is evaluated to #f, the evaluation of the remaining arguments is skipped. The result is #f anyway. Similarly, if any or's argument is evaluated to #t, no further argument gets evaluated anymore.

(and #f (/ 1 0)) => #f

(or #t (+ 3 "a") (/ 1 0)) => #tEven though some syntactic forms are not evaluated strictly, we can only define functions that are always evaluated strictly.

Apart from strict evaluation, there is another evaluation strategy called lazy that evaluates the arguments when needed. The argument's value is needed when we evaluate a function call of a built-in primitive function. Can we force Racket to evaluate some argument expressions lazily?

Suppose we want to define a function my-if that would behave like the regular if. Due to the strict evaluation, the following code works only partially:

(define (my-if c a b) (if c a b))

(my-if (< 0 1) 'then 'else) => 'then

(my-if (> 0 1) 'then 'else) => 'elseHowever, if we try the following:

(my-if (< 0 1) 'then (/ 1 0)) => /: division by zerounlike

(if (< 0 1) 'then (/ 1 0)) => 'thenmy-if does not work because it is a function whose all argument expressions get evaluated before its body. To overcome this issue, we need to postpone the arguments' evaluation. The trick, how we can do it, is to pass the argument expressions into the function as functions. Functions (more precisely, function closures) act as usual values, so there is no need to evaluate them anymore. Moreover, we can "hide" the argument expressions inside functions' bodies. Recall that the function body gets evaluated only when we call the function.

So let us try to pass into my-if the then and else expressions wrapped inside a parameterless function as follows:

(my-if (< 0 1) (lambda () 'then) (lambda () (/ 1 0))) => #<procedure>The result is better; no more division by zero error. Nevertheless, the result is a function. We can call it to evaluate its body:

((my-if (< 0 1) (lambda () 'then) (lambda () (/ 1 0)))) => 'thenWe can actually put the function call into the definition of my-if:

(define (my-if c a b) (if c (a) (b)))Now, we can apply it as follows:

(my-if (< 0 1) (lambda () 'then) (lambda () (/ 1 0))) => 'thenIt is awkward to wrap all the argument expressions into (lambda () ...). A parameterless function like (lambda () (+ 1 2)) is called a thunk. Racket even has a syntactic form creating a thunk from a given expression as follows:

(thunk (+ 1 2)) => #<procedure>It is equivalent to

(lambda () (+ 1 2))Thus we can simplify the above call of my-if a bit:

(my-if (< 0 1) (thunk 'then) (thunk (/ 1 0))) => 'thenStill, wrapping all the argument expressions by thunk remains tedious. We will see how to fix it once we discuss macros.

A natural question is why we need lazy evaluation. There are several applications besides functions behaving like conditionals.

- A typical situation when we must pass an expression into a function without evaluating it arises in concurrent programming. Suppose we want to evaluate an expression in a new thread. A function

threadcreates a new thread, and its single argument must be a thunk. For example, the following code creates a new thread, sums all the integers between 0 and 999, and displays the result on the screen once it finishes:

(thread (thunk (displayln (foldl + 0 (range 0 1000)))))- Another situation when lazy evaluation is useful is when we deal with a potentially infinite data structure. Lazy evaluation can simplify our code and make it more modular. Sometimes the resulting code might be more efficient. I will discuss such cases in the following section on streams.

Streams

A primary data structure exploiting lazy evaluation are streams. Streams are delayed sequences of elements. They are similar to lists, but their members are computed when needed. Streams could also be infinite. In other words, we can extract from them as many members as we need. Analogously to lists, streams are constructed through pairs. The first component carries data, and the second represents the rest of the stream. Unlike lists, the second component of a stream is delayed, i.e., wrapped into a thunk.

The thunks are further extended with a caching mechanism to make the computation with them more efficient. Once we evaluate the body of a thunk, the resulting value is cached. The cached value is used if we need to re-evaluate the thunk's body. Racket introduces a structure called promise. It is a pair consisting of a thunk and a flag whether the thunk's body was already evaluated. When we evaluate the body, the flag is switched, and the resulting value replaces the thunk.

A promise can be created by the function delay. Calling e.g.

(define p (delay (foldl + 0 (range 1000))))

p => #<promise:p>makes a promise called p whose thunk's body is (foldl + 0 (range 1000)). If we want to evaluate the promise and activate the caching mechanism, we call

(force p) => 499500 ; the body gets evaluated

(force p) => 499500 ; the cached value is returnedUsing delay and force, we can define streams manually. For example, the infinite stream of all natural numbers nats can be made as follows:

(define (ints-from n)

(cons n (delay (ints-from (+ n 1)))))

(define naturals (ints-from 0))If we try to evaluate naturals, we get a pair whose first component is 0 and the second one is a promise:

naturals => '(0 . #<promise:...ectures/lecture5.rkt:43:10>)

(car naturals) => 0When we need the next element from naturals, we force the promise:

(force (cdr naturals)) => '(1 . #<promise:...ectures/lecture5.rkt:43:10>)We do not have to construct streams manually as above. Racket has functions working with streams built in. They are mostly analogous to the functions for lists. The following table lists several of them together with their list equivalents.

| streams | lists |

|---|---|

| stream-cons | cons |

| stream | list |

| stream-first | car |

| stream-rest | cdr |

| stream-empty? | null? |

| stream-filter | filter |

| stream-map | map |

| stream-ref | list-ref |

| stream-take | take |

| in-range | range |

Using the above functions, we can shortly define the stream of natural numbers starting at n as follows:

(define (nats n)

(stream-cons n (nats (+ n 1))))Let us see how it works:

(nats 0) => #<stream>

(stream-first (nats 0)) => 0

(stream-rest (nats 0)) => #<stream>

(stream-first (stream-rest (nats 0))) => 1A finite stream can be converted into a regular list by the function stream->list. To make a finite stream from an infinite one, we can apply the function stream-take that restricts the given stream to its initial segment of a given length.

(stream->list (stream-take (nats 0) 5)) => '(0 1 2 3 4)

; but

(stream-take (nats 0) 5) => #<stream>Explicitly defined streams

The stream of natural numbers (nats 0) is an example of an explicitly defined stream. The definition is done recursively based on the function f as follows:

(define (repeat f a0)

(stream-cons a0 (repeat f (f a0))))The function repeat takes an initial element (repeat add1 0) where add1 is the built-in function

Implicitly defined streams

Infinite streams can also be defined implicitly by an equation. For instance, let

(define ones (stream-cons 1 ones))Similarly, if we want to define an infinite stream

(define ab (stream-cons 'a (stream-cons 'b ab)))

(stream->list (stream-take ab 10)) => '(a b a b a b a b a b)The definition of ab can be simplified using the function stream* that allows prepending several initial stream elements to an existing stream.

(define ab (stream* 'a 'b ab))We can also understand ab as a cyclic list. Cyclic data structures can be defined in a purely functional setting only through lazy evaluation. Another example might be an infinite stream (cyclic list) consisting of all weekdays:

(define weekdays (stream* 'mon 'tue 'wed 'thu 'fri 'sat 'sun weekdays))

(stream->list (stream-take weekdays 10)) => '(mon tue wed thu fri sat sun mon tue wed)If we extend algebraic operations on streams, we can invent more complex equations defining streams. For instance, we can add two infinite streams point-wise.

(define (add-streams s1 s2)

(stream-cons (+ (stream-first s1)

(stream-first s2))

(add-streams (stream-rest s1)

(stream-rest s2))))The function add-streams adds the first elements from the given streams and then recursively adds their rest. Using add-streams, we can redefine the stream of natural numbers

1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

+ 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 ...

-----------------------

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ...In Racket, the implicit definition of the stream of natural numbers based on the above equation looks as follows:

(define nats2 (stream-cons 0 (add-streams ones nats2)))Applications of streams

We have seen that streams provide an exciting way to deal with potentially infinite structures. Let us see some concrete situations where streams could be helpful.

Likely the most straightforward application of streams rather than lists is when we need to iterate through its elements, but storing the whole stream/list in memory is unnecessary. Consider the following code:

(foldl + 0 (range 10000000))It sums the first (range 10000000) of size (in-range 10000000) is reasonable in such a situation. It works like an iterator in Python, generating the elements on the fly.

(stream-fold + 0 (in-range 10000000))Comparing the performance of both approaches gives the following results:

> (time (stream-fold + 0 (in-range 10000000)))

cpu time: 171 real time: 169 gc time: 0

49999995000000

> (time (foldl + 0 (range 10000000)))

cpu time: 875 real time: 869 gc time: 640

49999995000000Newton-Raphson

Streams are further helpful because they can improve code modularity. When we need to generate a potentially infinite data structure, we must insert some tests into the generating code to stop the generation process. Consequently, the generating code and the tests are inseparable. On the other hand, if we use lazily evaluated data structures like streams, we can pretend that the infinite structure is first generated entirely, and then we do its post-processing independently. For more details on this idea, see the paper by John Hughes.[3]

Let us see some examples of this approach. Consider the Newton-Ralphson method for approximating the square root of a number

A terminating condition could be

Now, we compare the code that mixes the generating code with the terminating condition and the modular code utilizing streams.

(define eps 0.000000000001)

(define (mean . xs) (/ (apply + xs) (length xs)))

(define (next-guess n g) (mean g (/ n g)))

(define (good-enough? n1 n2 eps) (< (abs (- 1 (/ n1 n2))) eps))

(define (my-sqrt n [g 1.0])

(define new-g (next-guess n g))

(if (good-enough? g new-g eps)

new-g

(my-sqrt n new-g)))Line 1 defines my-sqrt (Lines 6-10). Line 7 computes the following approximation from the current one. Line 8 checks if the stopping condition holds. If it is the case (Line 9), we return our last approximation. If not, my-sqrt is recursively called again with a better approximation (Line 10.

We cannot separate the recursive generating process and the terminating condition in the above code. On the other hand, we can separate these two parts in an implementation based on streams. First, we generate an infinite stream of all approximations. Next, we independently process the resulting stream to find a suitable approximation satisfying the terminating condition.

To generate the approximations, recall the function repeat that produces a stream by successive applications of a function to an initial value. Utilizing repeat, we can generate the approximations converging to

(repeat (curry next-guess n) g0)

(stream->list (stream-take (repeat (curry next-guess 2) 1.0) 7)) =>

'(1.0

1.5

1.4166666666666665

1.4142156862745097

1.4142135623746899

1.414213562373095

1.414213562373095)Now, it remains to find the first approximation satisfying the terminating condition. To do that, we simply iterate through the stream, extract two successive elements and test the stopping condition. Once we find such an element, we stop the iteration and return the last approximation.

(define (within eps seq)

(define fst (stream-first seq))

(define rest (stream-rest seq))

(define snd (stream-first rest))

(if (good-enough? fst snd eps)

snd

(within eps rest)))Joining these two pieces gives us the desired square-root function:

(define (lazy-sqrt n [g 1.0])

(within eps (repeat (curry next-guess n) g)))It is reasonable to consider a solution using streams because of code modularity. When the solution is modular, the coder can independently focus on smaller pieces of code. This is mentally easier than devising one complex function. The above example should give you an idea of modularity. On the other hand, it is perhaps too simple to illustrate the advantage of streams, as the first solution is pretty straightforward.

Depth First Search (DFS)

For a more exciting example, consider a situation when our application needs to explore a graph of some states or configurations. For instance, we can look for a path in a digraph leading to a goal state, or the states can represent states of a game like chess, and we need to find the next move based on the graph exploration. During the exploration, we typically build a tree of already explored states as we explore the graph. We start in the initial state, which is the root node. Its children are the neighbors of the initial state. Other nodes are generated by getting neighbors of neighbors, and so on. This tree could be large or infinite, e.g., if the explored graph has cycles.

Without lazy evaluation, we usually generate the tree and simultaneously test conditions telling us when to stop the generating process. Using a lazily evaluated tree, we can first create the tree completely (even if it is infinite) and then traverse it to reveal the necessary portion of the tree nodes. Let us discuss an example using lazy evaluation to make it more concrete.

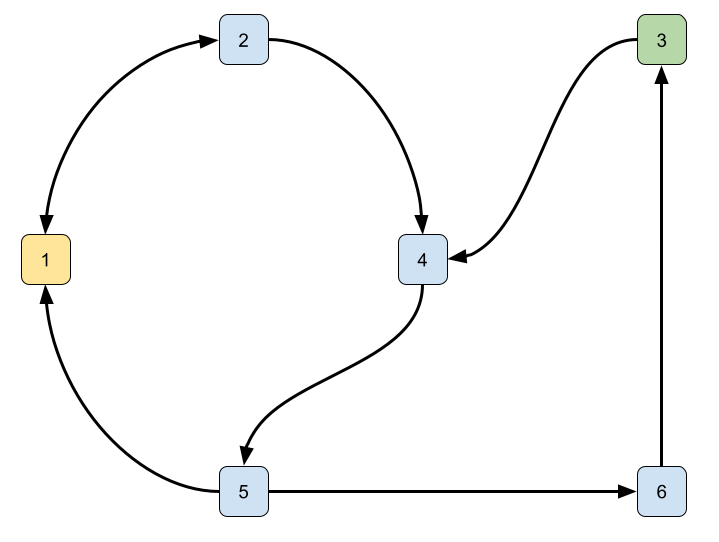

Suppose we are given a digraph to explore, i.e., we have a function generating neighbors of a node. Initially, we are in the state

To represent the above digraph in Racket, we introduce a structure capturing arcs and define a digraph g:

(struct arc (source target) #:transparent)

(define g (list (arc 1 2) (arc 2 1)

(arc 1 5) (arc 2 4)

(arc 4 5) (arc 5 6)

(arc 6 3) (arc 3 4)))Moreover, we define a function returning a list of neighbors of a given vertex:

(define (get-neighbors g v)

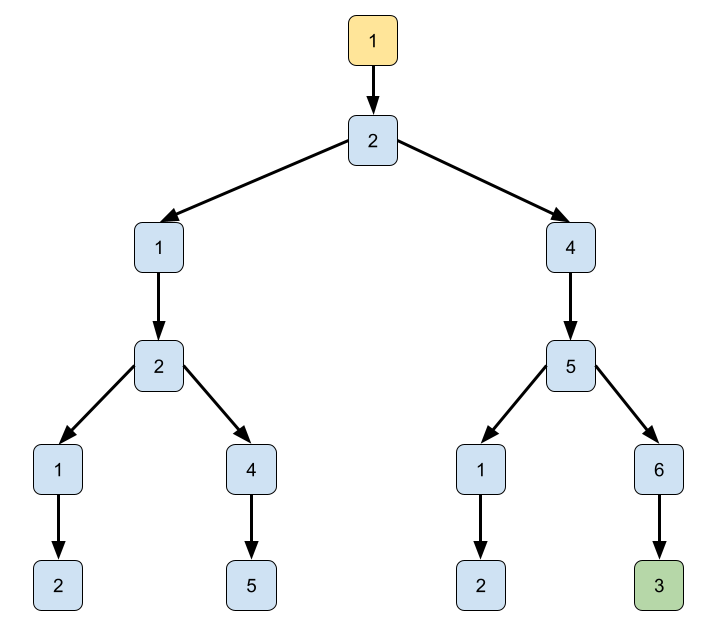

(map arc-target (filter (lambda (arc) (equal? v (arc-source arc))) g)))If we want to find the path, we build the tree by generating neighbors. From node

In the modular lazy approach, it is possible to implement a function generating such a (possibly infinite) tree and process it later. We represent the tree nodes as a structure

(struct node (data children) #:transparent)consisting of some data and a stream children of its children. Thus the children's evaluation is delayed. If we have a function generating children (I call them successors), it is easy to implement a function generating the whole lazy tree.

(define (make-tree get-successors v)

(define successors (get-successors v))

(node v (stream-map (curry make-tree get-successors) successors)))The function starts the generating process in a vertex v, computes its children (Line 2), and makes a tree node consisting of v and a stream of its children (Line 3). Even though successors form a regular list, we transform it into a stream by calling the function stream-map. Moreover, stream-map applies recursively make-tree to each child.

Using the function get-neighbors, we can generate the above-depicted tree as follows:

(define t (make-tree (curry get-neighbors g) 1))Let us evaluate the tree t manually in the REPL:

; the root node 1

t => (node 1 #<stream>)

; has only a single child 2

(stream->list (node-children t)) => (list (node 2 #<stream>))

; and the child has two children 1,4

(stream->list (node-children (stream-first (node-children t))))

=> (list (node 1 #<stream>) (node 4 #<stream>))Note that applying stream->list forces the children to get evaluated.

Once we have the tree, we can further process it. For example, we can prune or traverse it to find a desired node. As we want to find a path leading from node '(5 4 2 1).

We do not have to modify the generating function make-tree to do this node enrichment. It suffices to provide a different function generating successors.

(define (get-ext-paths g path)

(define end (car path))

(define neighbors (get-neighbors g end))

(map (curryr cons path) neighbors))This function takes a graph g and a path, extracts its last vertex end (Line 2), computes its neighbors (Line 3), and finally expands path by all neighbors, creating a list of possible path extensions (Line 4).[6]

Now we can generate the enriched tree as follows:

(define t-en (make-tree (curry get-ext-paths g) '(1)))Let us evaluate the enriched tree t-en manually in the REPL:

; the root node 1

t-en => (node '(1) #<stream>)

; has only a single child 2

(stream->list (node-children t-en)) => (list (node '(2 1) #<stream>))

; and the child has two children 1,4

(stream->list (node-children (stream-first (node-children t-en))))

=> (list (node '(1 2 1) #<stream>) (node '(4 2 1) #<stream>))It would be possible to traverse our enriched tree and search for the goal node. However, we must be careful as the tree is infinite. For example, the depth-first search might traverse forever (on the other hand, the breadth-first search would find the solution). Thus we first prune the tree. When searching for a path, we can omit paths containing cycles. We will implement a universal function filtering the node's children based on a predicate.

(define (filter-children pred tree)

(match tree

[(node data children)

(node data (stream-map (curry filter-children pred)

(filter pred (stream->list children))))]))Using pattern matching, we extract the root data and its children's stream (Lines 2-3). Lines 4-5 construct the filtered tree. Line 5 forces evaluation of the children and filters them based on the predicate pred. The children of remaining children are filtered recursively using stream-map (Line 4).

We use the function check-duplicates to test if a path is cyclic. It tests whether a given list contains an element more than once. Thus our predicate can be implemented as follows:

(compose not check-duplicates node-data)The predicate extracts the path from the node by node-data, checks the duplicates, and if there are none, it returns #t. Consequently, the filtered tree can be obtained by the following code:

(define t-en-f

(filter-children (compose not check-duplicates node-data) t-en))Let us see if the cyclic paths disappeared in the filtered tree. For example, the node whose path is '(1 2 1) should be removed.

(stream->list (node-children (stream-first (node-children t-en-f))))

=> (list (node '(4 2 1) #<stream>))So it works well. We cut off the left branch of the tree as expected.

Finally, we implement a function dfs traversing the filtered tree. More precisely, the function executes the depth-first search. It has two arguments. The first is a predicate recognizing a goal state. The second is the tree to traverse.

(define (dfs goal? tree)

(match tree

[(node path children)

(if (goal? path)

(reverse path)

(ormap (curry dfs goal?) (stream->list children)))]))Using pattern matching, we deconstruct the tree to get a path and its children (Lines 2-3). If the path satisfies the predicate goal? (Line 4), we are done returning the path in the usual order (Line 5). If not, we force the children to be evaluated and search recursively in the children (Line 6). The function ormap behaves like the regular map. It applies the function given in the first argument to the list's members sequentially. However, it does not create a list of images. It just returns the first image different from #f. If all the images are #f or the list is empty, the result is #f. Thus if we get by recursion to a non-goal node having no children, ormap returns #f, and we return #f to the previous recursive call.

Now, let us test our solution on the graph example:

(dfs (compose (curry eqv? 3) car) t-en-f)

=> '(1 2 4 5 6 3)It correctly finds the path from node

Note that also,

fmight be a compound expression computing a function to be applied to the arguments specified by the expressionsexp1 exp2 ... expN. For example, consider the call((curry * 2) 3)where the function is given by the expression(curry * 2). ↩︎This type of computation occurs in Fixed-point iteration, a method of computing a fixed point of a function. For example,

(repeat cos 0.1)generates a stream converging to the Dottie number, i.e., the fixed point of the functionsatisfying the equation . ↩︎ John Hughes: Why Functional Programming Matters. Comput. J. 32(2): 98-107 (1989) ↩︎

Instead of

, we could also use e.g. . However the accuracy of the latter depends on the size of g_i, while the former is accurate for all values of. ↩︎ The dot in the definition

(mean . xs)tells Racket thatmeancan have an arbitrary number of arguments. The list of their values is bound toxs. Thus to sum them, we need to call(apply + xs). ↩︎The function

curryris just likecurry. It transforms a function into curried form but considering its arguments in the reversed order, i.e., from right to left. ↩︎